Paul Gauguin started his artistic journey as a thirty year old Parisian with only a part-time interest in painting. This inauspicious start quickly bore remarkable fruit, kickstarting a career which eventually signposted Modernism.

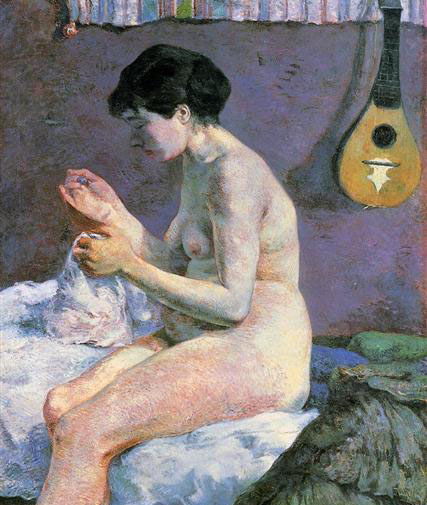

‘Woman Sewing’ from 1880 is one of his first remarkable pieces. The figure has real fleshy weight yet she also manages to shimmer with life. The picture suggests something tighter and more enduring than the ethereal Monet and Pissarro, whilst also offering a premonition of Seurat’s Divisionist dots. Perhaps most amazingly, this was all achieved while Gauguin was still a full-time stockbroker.

As Gauguin’s story unfolds, I can’t help feeling sorry for his wife, Mette. She probably thought she’d married a middle-class career man who would settle down to a quiet bowler-hatted life in Paris suburbia. But when this late starter hit his 40s, he abandoned his career and family, and left bourgeois society to start a gradual flight from civilization that was to consume him.

This process began in Pont-Aven in Brittany, where he painted the traditional garb of the Breton women and found himself at the heart of an artist’s colony. Later in the 1880s (after a famously ill-fated attempt at living and working alongside Van Gogh) he ended up in Le Pouldu, an even more remote agrarian outpost.

The next logical step, then, was to leave France and search overseas for an ideal of the ‘primitive’ existence. What exactly was he searching for? Quotes from Gauguin regarding the subjects he encountered in his new home of Tahiti make me wince. His ‘Tahitian Woman with a Flower’, for example, is referred to in a letter as ‘not very pretty by European standards.’ (Whereas I’m quite sure she thought he was God’s gift, right?) This picture itself remains, nonetheless, a great portrait, for it expresses something of this weird culture clash. Gauguin’s mark-making may have reached its mature style, with simplified bold colours, outlined shapes and stylized forms. Yet if his desire is to chase what he called, ‘the primitive’, it’s clear he’s stopping some way short. This is a very Western portrait, a dweller on a remote island posed as though for a Renaissance painter – soberly covered with a blouse, her hands folded in an undeniable, and possibly very conscious, echo of the Mona Lisa. He sees her, but does he really ‘see’ her? And, for that matter, does she see him? This picture seems to sum up the contradiction at the heart of much of Gauguin’s late Tahiti output, and I guess it’s the reason I’ve always found it difficult to connect with these works. Tahiti is to him an idea, and not a reality. I’m not inclined to take his word for any of it.

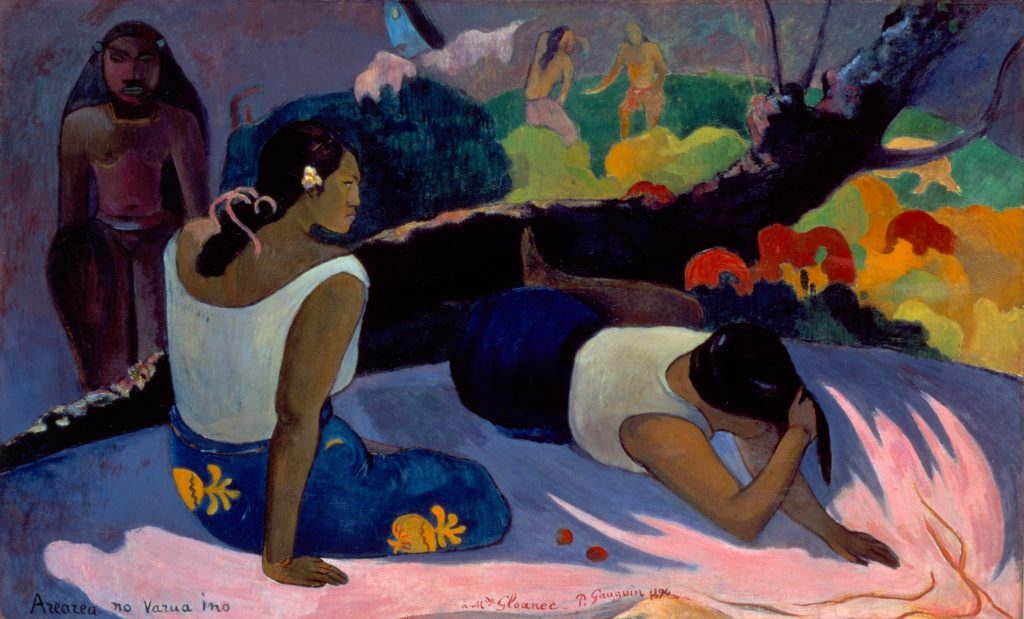

Yet, as I’ve studied Gauguin’s output I’ve come to realise slowly that maybe I’ve been missing the point. He wasn’t documenting island life like a news reporter. He was myth-making, living out a dream existence.

‘Self Portrait with the Yellow Christ’ dissects the self-mythologising of this middle-aged Gauguin. Audaciously, yet rather wonderfully, it completely encapsulates his perception of his own importance. He is flanked by two examples of his own work, their feet in very differing traditions. On the left, his ‘Yellow Christ’ stands for the Western tradition. To the right his sculpture of a ‘Grotesque Head’ is influenced by Polynesian art. He looks out from between them, not with an arrogant sneer but with serious determination.

Gauguin was the model for both the ‘Yellow Christ’ and the head sculpture, making this a kind of triple portrait – with the public face at the centre, and his two hidden good and bad artistic faces flanking him like the opposite sides of a coin. He seems to volunteer himself as the one who can bring these two traditions together, travelling off on his artistic voyage partly in the guise of a long-suffering Christ figure. ‘It’s a hard job’, he seems to say, ‘but I’ll do it.’

Life in Tahiti was harder than Gauguin expected, however. He never had enough money. He hoped his work would cause a sensation in France, but it was largely ignored by the public and scorned by the critics. He lost his dealer and, possibly due to the onset of syphilis, his health began deteriorating. There was an alleged suicide attempt. That’s how wonderful his paradise proved to be.

Retreating to the even more remote Marquesas Islands, he consoled himself with sexual exploits, taking teenage girls as wives and living in a hut he dubbed ‘the house of pleasure’. It’s a pretty sordid story, really.

Looking at many of the sun-drenched Tahiti pictures, it’s clear there’s a disconnect between this squalid life and the painted spin he put on it, which makes for a strange viewing experience. Gauguin was not an artist who wanted to reflect his reality in art. The fabricated element of these works is nowhere better expressed than the fact that a handful of his ‘Tahiti’ pictures were actually produced during a return trip to Paris. The artist was painting his life as he wanted it to be seen, not as it really was. Tellingly, he once told Van Gogh that he sought to convey ‘the wildness I see, which is also in myself.’ The search for some form of basic ‘primitive’ life untouched by Western civilization was not, perhaps, an external search at all. It was a flight into the imagination.

Gauguin died in 1903. Just a few years later, in 1907, Picasso saw his late work and incorporated elements into his ‘Demoiselles d’Avignon’ – the picture which kick-started Modernism. Picasso’s biographer John Richardson writes that Gauguin showed him how ‘disparate elements… could be combined into a synthesis that was of its time yet timeless.’