Michael’s Landy’s installation ‘Art Bin’ (2010) was a self-described ‘monument to creative failure’, into which members of the public were invited to discard unwanted artworks. It got me thinking about all the ways that, through history, works of art have been lost, destroyed, discredited and mothballed.

It’s no surprise to learn the curious alchemy of the gallery, which can transform an everyday object (an unmade bed, a pile of bricks) into a valuable cultural treasure, is prone to slip-ups in the opposite direction. Fluxus artist Gustav Metzger exhibited a transparent bin liner filled with waste as part of a 2004 installation at Tate Britain – only to discover that, just prior to the exhibition opening, a hapless cleaner had whisked it off to its rightful place in a waste compactor. Anish Kapoor had a taste of this, too, when an art handler placed one of his sculptures in a skip, and later had it destroyed at a waste plant.

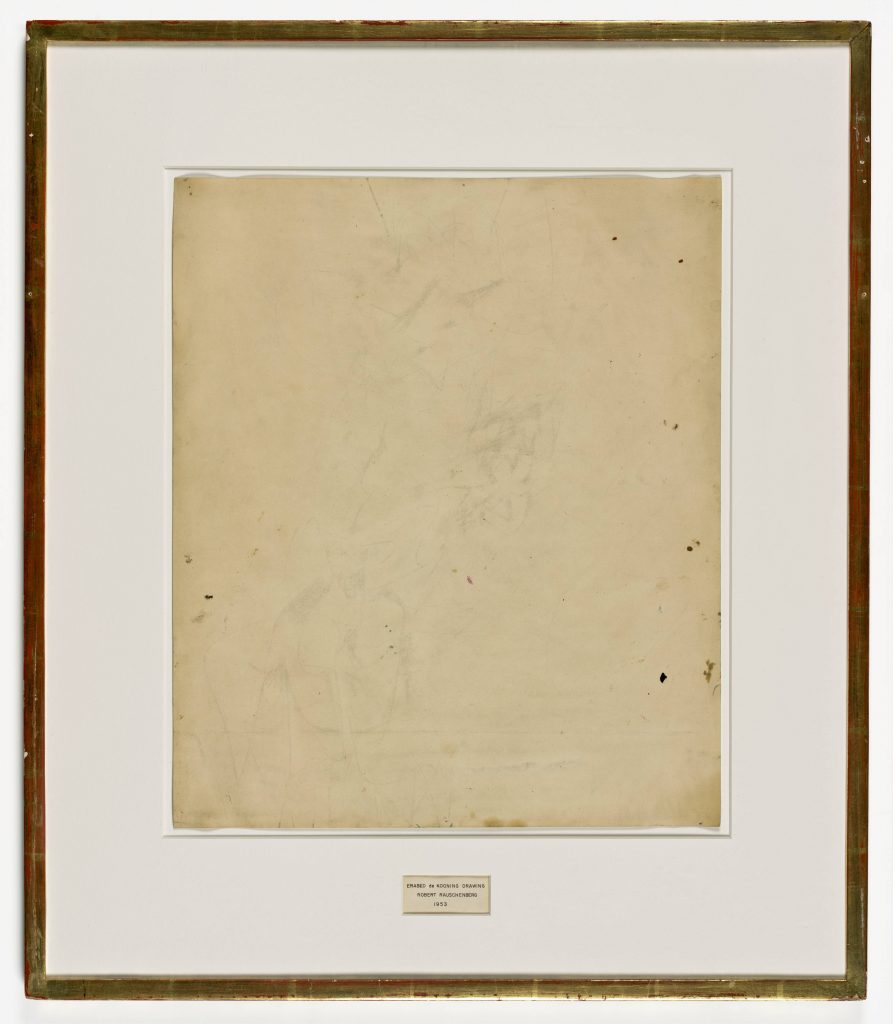

Intentional art vandalism forms its own distinct category in art-binning. One particularly famous act of art destruction occurred in 1953, when artist Robert Rauschenberg completed his ‘Erased de Kooning’. Willem de Kooning had achieved notoriety in the abstract expressionist movement. Rauschenberg was a generation younger, and an aspiring artist loosely associated with Pop Art who wanted to rebel against the older artist. He got hold of a de Kooning sketch, intentionally choosing a graphic piece drawn in thick dark lines. He then spent several days applying elbow grease to the challenge of rubbing it out completely. Finally, with the original a mere ghost on the page, he signed it with his own name, in the process making an undeniable statement about his own intentions towards the preceding generation.

Fortunately, examples of artists destroying the works of their contemporaries are rare. One recent example involves the American pulp crime novelist Patricia Cornwell, who spent over two million pounds buying dozens of works by Victorian British artist Walter Sickert in an attempt to harvest DNA evidence linking him to the Jack the Ripper murders. She allegedly destroyed several Sickert works in her research process and still failed to discover any linking forensic evidence.

In the often-difficult financial relationship between a commissioned artist and his/her client there are plenty of examples where the end product has been shut away in disgust, or destroyed altogether. One masterpiece lost to the nation in this fashion (and recently dramatised in ‘The Crown’) was a major portrait of Winston Churchill by Graham Sutherland, gifted by the Houses of Parliament to the sitter on the occasion of his eightieth birthday. The picture was seen on the day of the ceremonial presentation – but never again. Years later it was revealed that Churchill and his wife had destroyed it. “It makes me look half-witted!”, he said at the time. Another Tory MP described the work as “a study in lumbago”, whilst Lord Hailsham judged it “disgusting” and “ill-mannered”.

Public taste can be even more difficult to gauge. Rachel Whiteread’s ‘House’, a disused terraced house filled in with concrete, was removed less than a year after its completion at the insistence of the local council. Meanwhile Richard Serra’s ‘Tilted Arc’, a large block of free-standing steel, lasted eight years on Federal Plaza New York before being removed as an eyesore.

Artists, of course, frequently destroy their own work, usually in an attempt at quality control. Francis Bacon was particularly famous for taking a scalpel blade to any artworks that didn’t completely satisfy him, to prevent them from reaching the marketplace and thereby damaging his own reputation. In ‘The Gilded Gutter Life’, Daniel Farson describes the moment when Bacon, strolling down Bond Street, saw one of his unfinished canvases for sale in an art dealers. Bacon marched in and bought the canvas for £50,000 cash from the bemused gallery owner. He dragged it outside and shredded it with his bare hands on the street. (Farson guesses that there were over seven hundred Bacon pictures destroyed at the artist’s own hands).

Accidental destruction or loss is a sadder aspect of art-binning. World War II in particular saw the disappearance of dozens of famous artworks from the Renaissance and beyond. As a child flicking through art books, I found these artwork ghosts quite fascinating – only ever reproduced in grainy black and white, with their eerie captions ‘destroyed by fire’ or ‘whereabouts unknown’.

More recently, one of only two tapestries by Joan Miro was lost in the World Trade Centre attacks of 9/11, while dozens of artworks by the YBAs were lost in the Momart warehouse fire. The Momart fire claimed Tracey Emin’s recognizable ‘tent’, “Everyone I Have Ever Slept with”, from the original Sensation exhibition. (In a surreal but perhaps inevitable coda to this disaster, one young artist called Stuart Semple tried to make a new artwork from the ashes of the fire. A legal challenge was apparently launched to determine who ‘owned’ the ashes…)

The question of attribution raises the ghost of a very different kind of art-binning. Some artworks find themselves consigned to the dark basements of art collections when critics decide that they were not, in fact, painted by a famous master. Spare a thought, in that case, for several hundred paintings by Rembrandt, whose authenticity have all been officially doubted by the ‘Rembrandt Research Project’. In 1995 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York addressed this in their exhibition ‘Rembrandt/Not Rembrandt’, which bravely hung the master’s canonical work alongside the falsely attributed paintings and invited the public to decide if they could really tell the difference.

Is there ever any way back from the art bin? It does cut both ways, and there are many great examples of lost artworks being rediscovered. In 1919 LS Lowry painted his friend Frank Jopling Fletcher. At the time he was considered a Sunday painter by his friends, and the commission little more than a favour between pals. The sitter’s wife hated the end product and recycled it to make a wall for her chicken coop in the back garden. Decades later the likeness was rediscovered beneath a patina of bird shit and restored to take its place alongside the artist’s other works at the Lowry centre in Salford.

An even more far-fetched story can be told of the great lost Leonardo painting of St. Jerome. In the early 20th century a collector in Italy noticed a painting of a torso as part of a table top in a flea market. Later he found the corresponding head being used as part of a bench. Amazingly the pieces, when put back together, formed the complete lost Leonardo sketch – now safely preserved in the Vatican.

Some lost masterpieces have even managed to hide in plain sight – like a major early work by Picasso, ‘Last Moments’. The 1900 oil on canvas was the artist’s entry to the Universal Exposition in Paris, but had only been listed descriptively in archive documents – no-one had ever seen it. Eventually x-ray technology revealed that Last Moments had been painted over by Picasso himself in 1903 when poverty compelled him to recycle his old canvases. ‘Last Moments’ is now another masterpiece, ‘La Vie.’ Two for the price of one.

2 thoughts on “Art Bin”

Good article! I remember another Churchill portrait painted by Walter Sickert. That one was not liked by his wife, but it’s still intact.

Oh yes, I just looked this up. Thank God it survived. Churchill must have been a blooming nightmare client.