Goya paints Manuel Godoy, arguably the most powerful man in Spain, and certainly one of the most hated. Godoy, was a charismatic member of the royal guard who inveigled himself into the affections of King Charles IV and his wife Maria Luisa. In the space of a few years he had become Prime Minister of Spain and, thanks to his Royal influence, the de facto dictator of the country. He was rumoured to be the Queen’s lover, and for a time he forced his wife to live in the same house as his mistresses. King Charles showered him in gifts and bestowed a ludicrous list of meaningless official titles on him – foremost among them ‘Prince of the Peace’, which probably sounded ironic to the Spanish populace, given that Godoy had dragged Spain into several bloody wars with France, Portugal and England.

In Goya’s portrait he leans back in a victory pose intended to echo the triumphal portraits of antiquity. It’s a bit awkward, though, and falls far short, surely, of convincing us that this sitter possesses genuine heroism. It looks like Goya can’t bring himself to believe in the myth of his sitter’s brilliance. He looks like a hard drinking, over-eating, slightly distracted posh boy, who’s just collapsed in a rather ungraceful heap.

Many of Goya’s images present us with these curious riddles regarding his true intention towards his sitters – which is why I find him such an intriguing painter. So much official portraiture of the past exists to convince us of the power and charisma of the ruling classes, but generations of onlookers have cast doubt on whether Goya was enacting a kind of 18th century version of trolling. Debates have raged for centuries, for example, about his portrait of the family of King Charles IV, once described by Theophile Gautier as ‘the corner baker and his wife after they won the lottery.’ At first glance it does seem that in its faithful transcription of royal ugliness it shows not realism but actually open, treasonable contempt.

Some critics have challenged this view, notably Robert Hughes in his definitive biography of the artist. ‘The idea that Goya set out to satirise the patrons he depended on’ he write, ‘is of course the merest nonsense’. Much as we’d love Goya to be a sort of 18th century art terrorist, smashing the system from within, Hughes argues that it doesn’t seem likely he’d have got away with it and kept his job. Simply put; these people were just bloody ugly, and he painted them, as requested, to the life.

It remains, like many things in visual art, a mystery. I think the fact that generations of onlookers have been compelled to ask these questions time and again tells its own story, though. I can’t overcome the sense that something weird and intangible is happening in these portraits.

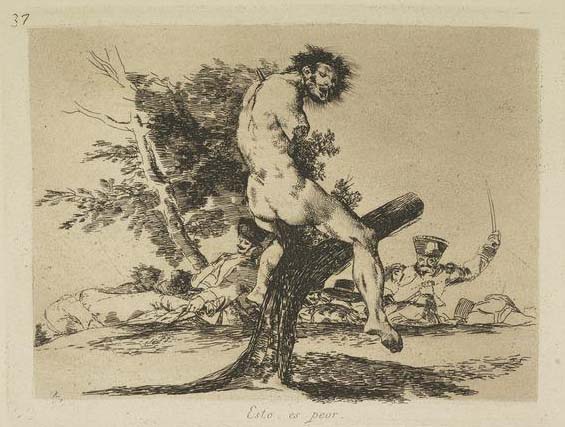

Goya was a republican. Whilst we have no written evidence of his disdain for the excesses of the Spanish monarchy, we know that many of his friends were radical Enlightenment figures critical of the conservatism of church and Crown in Spain. He produced artworks in favour of the Constitution proclaimed at Cadiz in 1812, and criticized the war and the subsequent Restoration of the monarchy in his Disasters of War prints.

Goya’s life story seems relevant to all this too. In a Spain where male middle class life expectancy was 40, he lived to 82. If he’d died during that normal life range, he’d have been an unmemorable artist. In his 40s, however, he suffered from a serious illness which temporarily derailed his career and left him stone deaf. Only then, surviving an extra 40 years, did his genius properly emerge, in a series of paintings and graphic works which are at times perplexing and at other times satirical of every aspect of the age he lived in.

Late in life he executed the Black Paintings (including ‘Saturn eating his children’) on the walls of his own house. Was he locked in an insane world of nightmares and paranoia? Or, as the Disasters of War etchings might suggest, was he merely reacting to the insanity of the cruel age he dwelt in?

Imagine being completely deaf and living in a war-zone, seeing mutilated bodies hanging from the trees, and then being asked to paint pompous overblown generals like Manuel Godoy. Your deafness would prevent you from hearing their self-justifications or the squirming machinations of their enormous egos. A horrendous gory mime show enacted before your eyes. You’d see past all the trappings, as Goya did – and you wouldn’t even need to caricature it in order for your contempt to somehow reveal itself on the canvas.

Our portrait shows Godoy at the age of 34, during his second spell as Prime Minister, just after he invaded Portugal. He is handed the note of surrender and sits down on a chair at the edge of the battlefield. Does this portrait flatter its subject? Despite the awkwardness of the pose and the unconvincing notion of Godoy as military hero, it probably still does, through gritted teeth, offer flattery of a sort. There is a terrible, dark, dick-swinging bravado to the masculine indolence of this man’s posture – crudely emphasized by the stick positioned between his legs.

Godoy never got his comeuppance, though he came very close to being lynched in the 1808 Mutiny, when the Spanish people finally had enough and marched on his residence. The King and Queen remained under his spell to the last, and abdicated their throne to spare his life. The three of them were forced into lifelong exile. Forty years later this cruel man, once among the most powerful and feared men in Europe, finished his life as a dotty man in his eighties, living alone in a small flat in Paris.