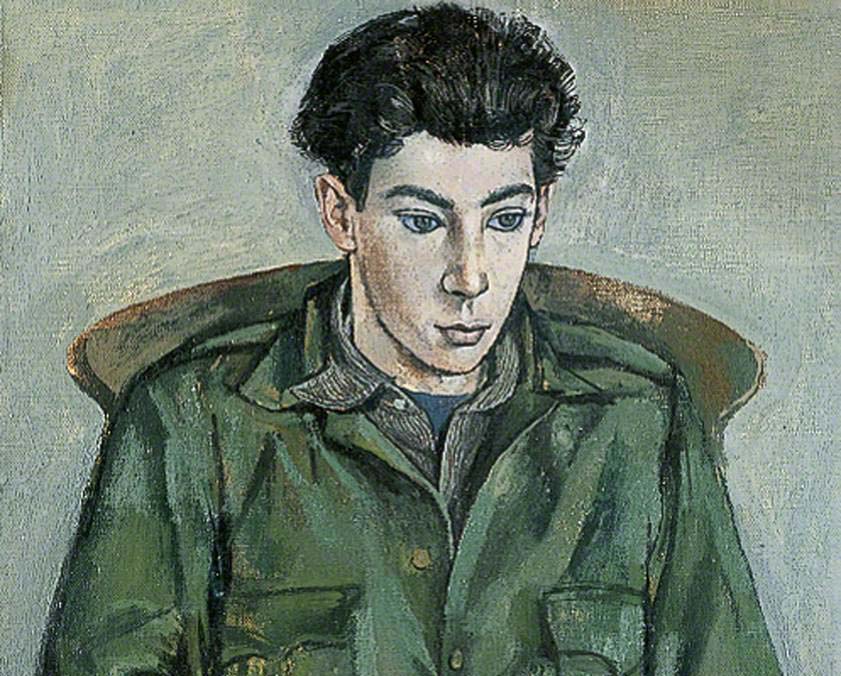

In 2003, during a visit to Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, I encountered a small portrait which stopped me in my tracks. What was the strange, stifled emotional longing I sensed in this polite, reserved image from 1952? It seemed almost spooky. I welled up with tears during that first encounter, experiencing the strange shock of an unexpected reunion with an old friend.

The sitter, whose name is David Tindle, looks a little stiff and isolated in his own world. His shoulders seem tense and his hands are awkwardly clasped in front of him. Perhaps the studio is unheated, after all, he’s got three layers of clothing on. The muddy colour palette adds to the sense of froideur between sitter and artist.

The portrait is by John Minton. He belonged to a postwar generation of figurative painters who socialised together. Their number included, famously, Bacon and Freud. He was independently wealthy but chose to divide his time between fine art and commercial art, a practice which had yet to be named ‘illustration.’

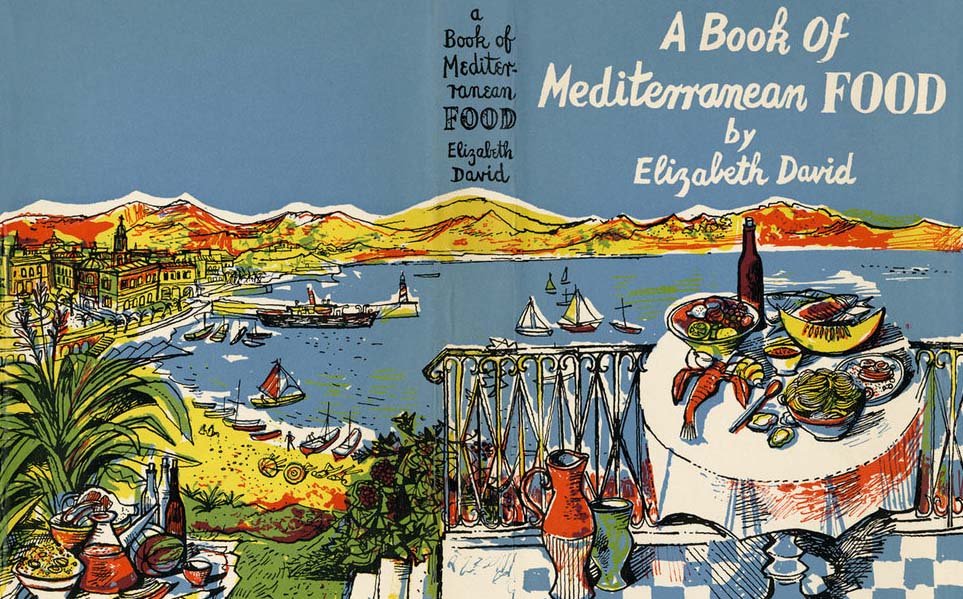

Minton is now well remembered for his illustrations on various book jackets, including the first editions of the famously pioneering Elizabeth David cookbooks. Such perceived commercial sell-outs were teased by his fellow ‘serious’ artists like Bacon. Freud was openly dismissive of his skills as a portrait artist.

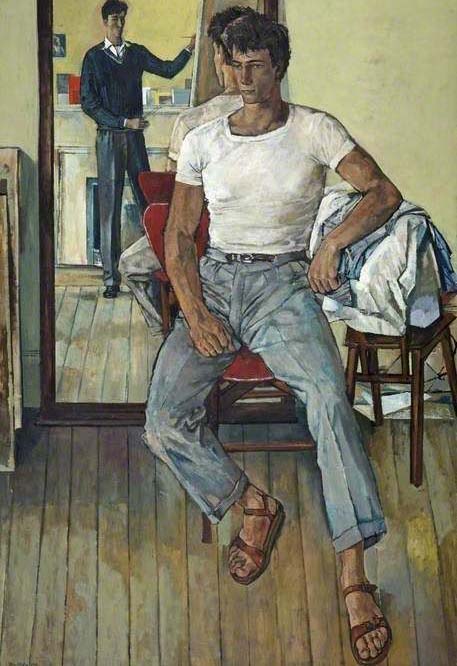

You’re unlikely nowadays to see Minton canvases on display in the major London art galleries. He was collected by the Tate, but their holdings of his work rest in the warehouses, far from public view. You might be more lucky in regional galleries. My home town, Bournemouth, used to display a Minton portrait of a chap called Norman Bowler in the Rusell-Cotes museum – a painting I’d known since childhood.

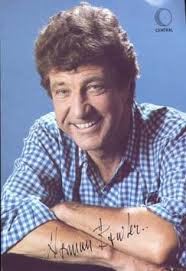

This portrait of Bowler, painted at a larger scale, seems less engaging and enigmatic than the portrait of Tindle, somehow. Yet as a teenager the picture still fascinated me on account of the identity of the sitter.

Norman Bowler was a body-builder in the 1950s, famously good-looking. Minton clearly took a shine to him, and featured him in several artworks. He married Minton’s best friend Henrietta Moraes, one of the most notorious figures in Soho society of that period. She was a muse to Francis Bacon, a wildly promiscuous good-time girl who later descended into alcoholism.

Henrietta’s marriage to Bowler was shortlived. He later went into acting, eventually being cast as a long running character, patriarch Frank Tate, on Emmerdale in the early 90s. You couldn’t make it up.

So who was David Tindle, the sitter in my Chichester portrait? In the original 2011 version of this blogpost, on my old blog, I had nothing but supposition to go on. A Google search told me very little. There was an 80 year old Royal Academician who shared his name, so maybe that was him, I wondered.

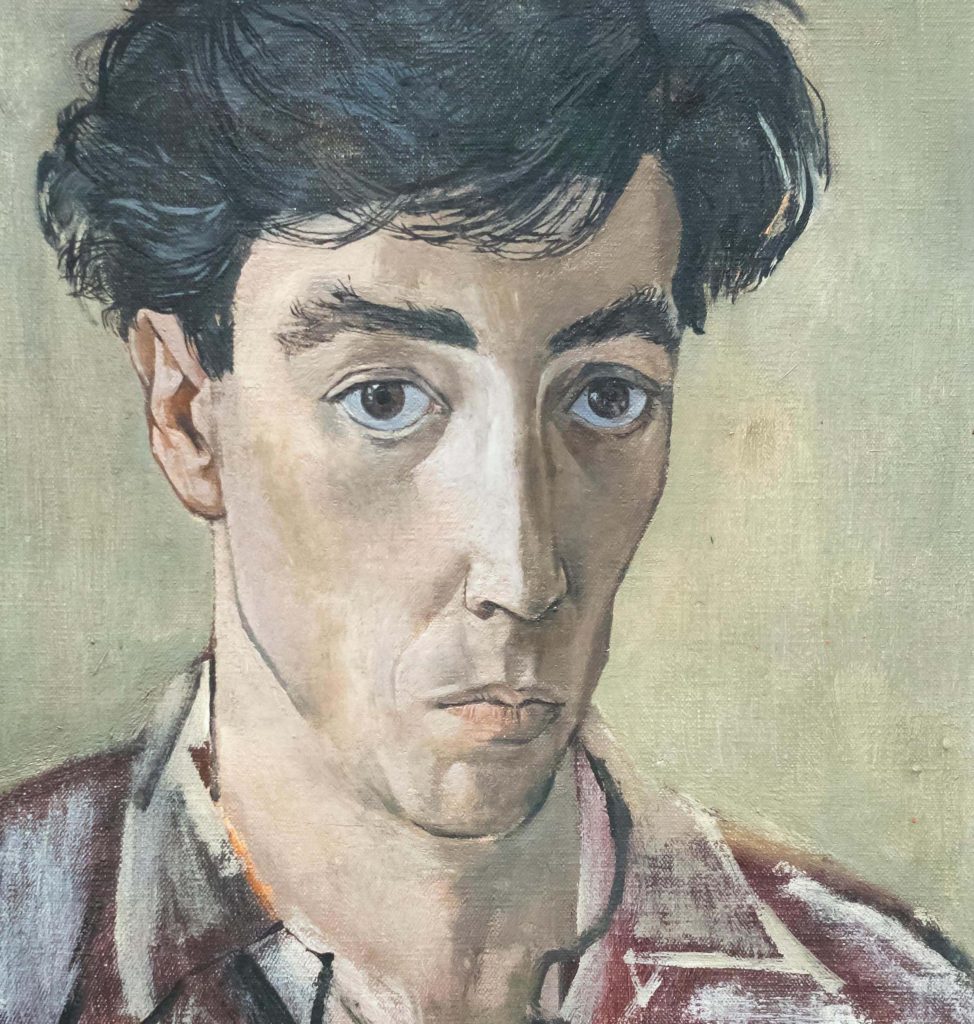

Amazingly, though, my blogpost garnered some fresh info. David’s daughter Saskia Tindle messaged me to confirm that her artist father was indeed Minton’s protégé and muse in the 50s. Another friendly message pointed me to a contemporaneous self-portrait by David in the Ruth Borchard collection.

I’m delighted to know that David Tindle is going strong, and at the age of 89 may even be enjoying a late career re-evaluation. Huddersfield art gallery ran a successful retrospective of his work back in 2017. In a five star review for the Guardian, Rachel Cooke called it ‘one of the loveliest small exhibitions you’re likely to see this side of Brexit’.

Minton wasn’t quite so fortunate. He seems to have suffered with mental health issues and, as a gay man at a time when, let us not forget, it was still illegal, he often suffered the pain of unrequited love. He was apt to give his heart away to unsuitable, or heterosexual, men and spend large sums of money on people he liked, only for them to disppoint him.

I didn’t know any of this when I first happened upon this portrait. My own emotional response was natural, and completely uninformed by Minton’s biography, but for me it seems to fit. The sitter seems detached, somehow. Admired and (with those big eyes) even idealized by Minton – yet utterly lost to him.

In his book on Francis Bacon, Daniel Farson writes of the final heartbreak in the artist’s life. In 1957 Minton’s best friend Henrietta Moraes (who had also been married to the aforementioned Norman Bowler) won the heart of a man Minton was also in love with. In the words of Julian Maclaren Ross he was emotionally ‘torn to pieces by tiny marmosets’ and, perhaps in a cry for help gone wrong, took an overdose of sleeping pills and died.

I reshared my original Minton blogpost one more time, in 2016, and the story took further turns. Around this time I met Simon Martin, the director of Pallant House. He was putting together a retrospective of Minton’s work, and whilst looking into David Tindle he’d come across my blogpost. I enjoyed a cup of tea round at Simon’s place one morning as he was beginning to select items for the show, and a few months later I was delighted and more than a little moved to attend the show, which beautifully re-appraised this artist’s career, bringing out many paintings and prints which had languished in storage for decades. It was particularly moving to know that Norman Bowler was able to attend the private view and see one of the portraits of him in situ (David Tindle was sadly unable to attend).

Not long after this, the actor and writer Mark Gatiss presented a documentary about Minton on BBC4, which contributed greatly to a resurgence in the popularity and status of his work. There’s a huge amount of information about Minton out there online these days, compared to the slim pickings of my initial 2011 searches. I was delighted, for example, to find this short video of Tindle himself talking about the portrait.

Looking back, I believe that Minton’s portrait, and the emotion it succeeded in encapsulating for me that day in Chichester some 17 years ago, was surely one of the reasons I came to focus my own energies on portraiture. It’s come to have a talismanic importance in my life. It feels strangely appropriate, therefore, that in 2019 I got an opportunity to complete a commissioned portrait of the Pallant House director Simon Martin. I still live in hope that I may myself get to one day meet (and maybe even sketch or paint) David Tindle.