The Russell Cotes gallery in Bournemouth is a unique little jewel, a crazy time capsule and kaleidoscope, a kind of late Victorian Conceptual Art installation. But if you go there expecting to be wowed by the art collection of a late 19th century sophisticate, you may be disappointed. All debate on this point is neatly resolved by the visitors brochure, which informs me that one of their toilets is a ‘must see’ highlight of the museum. One of their other five chosen highlights is, without irony, ‘the view from the garden.’ The house is covered in a dense collection of paintings some of which, even if I chanced upon them in a charity shop, would be all too easily passed over.

I grew up in Bournemouth, so this is an art collection about which I’ve had decades to deliberate. The place is an intriguingly frustrating cavern of paintings that, once upon a time, were fashionable. I used to hate it but now I have to concede my feelings are less easy to categorise. In the form of painter Edwin Long, this museum offers up one particularly juicy tale of what can happen to an artist’s reputation after they die – a tale Damien Hirst would be wise to heed.

Edwin Long was a star painter of his day. He held the British record for the highest price paid for the work of a living artist. His picture ‘Anno Domini’ caused a sensation when it was displayed in a Bond Street Gallery. Art lovers queued round the block to marvel at this masterpiece, and paid money just for the privilege of seeing it for a few moments.

Now ‘Anno Domini’ sits gathering dust in the main gallery at the Russell Cotes. I pause there for a moment and watch the gallery-goers drift past, disinterested. Some don’t even reward the picture with a glance. This once famous artist is forgotten and his work looks outrageously… well… Victorian. The figures throw over the top, am-dram gestures. It feels dreary, hectoring and lifeless. It just didn’t stand the test of time. Sorry Edwin.

I can imagine Sir Merton buying this transiently fashionable work and delighting in the prospect that he would be leaving Bournemouth with a world-beating art collection. Maybe he just liked it, of course – in which case, fine. Either way, the end result is that we get to see The Art That Time Forgot, and these days I no longer hate it. I can kind of relish the experience.

Sometimes Sir Merton did get it right. Albert Moore’s ‘Midsummer’ is acknowledged by all as the standout masterpiece in the collection, a bold and life-affirming canvas with kissably lovely orange fabrics painted with a joyful panache.

Where this museum really comes into its own, though, is as a portrait of the quixotic Sir Merton. It’s greater than the sum of its parts. The whole building is his brainchild, from the garden to the patterns on the fabric – and it’s the honest and enduring record of a frustrating, complex character. Merton and his wife Annie helped, quite literally, to put Bournemouth on the map. At the start of the Victorian period, the town basically didn’t exist. It was some heathland, a couple of houses and a pub. By dint of the efforts of just a few Victorian men, it became a growing holiday destination for the new wealthy classes. Sir Merton owned the Royal Bath Hotel, still Bournemouth’s grandest place to stay.

Already a wealthy couple by this stage, the Russell-Cotes indulged their joint passions of travel and collecting. In 1885 they toured Japan, only seventeen years after the end of the samurai period. It must have been an utterly fascinating, at times dangerous, undertaking. They returned with case loads of purchases – lacquer boxes, statues, pottery and portable shrines.

It is clear that, as collectors, they lacked focus. The gallery labels inform that they kept few records and failed to label things. Many of the things they bought lacked a provenance, and have therefore been a nightmare for subsequent curators. It looks like they bought things in a flashy, Michael Jackson way. Wandering into their Japanese gallery, this is all too obvious. A mish mash of Oriental kitsch is laid out behind a glass screen. It looks like a hoarder’s lumber room. Across the glass is a laminated caption – an 1885 quote from the manager of a bank in Yokohama. They have bought, this man beams, ‘no doubt some priceless Japanese treasures.’ The writer of this quote doesn’t sound convinced. There could almost be sarcasm in the phrasing. Merton and Annie bought some nice things, but… ‘priceless treasures’? No.

The weird, trippy nature of this collection makes it what it is. Resign yourself to the madness, and it’s a joy. Next to the Japanese bric-a-brac dump is a shrine to the Victorian actor Sir Henry Irving – another largely forgotten figure. Both mocked and praised in his lifetime for a mannered acting technique, his biographer Bram Stoker is said to have used him partly as the inspiration for Dracula. A text eulogy to the man is painted on the wall, next to another jumble of artefacts. It’s all nice, if a little toady-ish.

Henry Irving was known in his day for being an actor-manager who oversaw every aspect of his plays, and perhaps this is why he enjoyed such a friendship with Sir Merton. Control freakery and a healthy dose of ego are hallmarks of this museum. Other museums simply let the artefacts speak for themselves. Not here. The painted text on the wall of the Irving room reminds us that Merton wants to directly guide our experience of this place. Meanwhile, the main gallery is emblazoned with more text to tell us it was opened by Princess Beatrice. ‘A Princess was here, in my house!’ it seems to shout, needily.

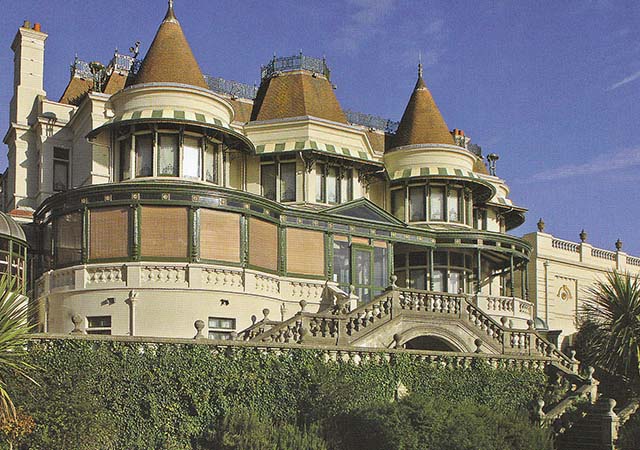

The East Cliff Hall, as this building was originally known, was gifted by Sir Merton to his wife as a birthday present. Completed in 1901, it is one of the very last examples of Victorian architecture. It sits right at the absolute tail end of a great era. The exterior, like the interior, is a mish-mash of styles. Merton worked closely with the architect and described it as a mixture of ‘the Renaissance with Italian and Scottish baronial.’ It must have been a hard job to be micro-managed by Merton on this bonkers build. Yet, in attempting to car crash his three favourite architectural styles together, he created an odd synergy with the patchwork mismatch of the interior display. It’s nuts but it kind of works. It’s a fully realised immersive environment of show-offy maximalism.

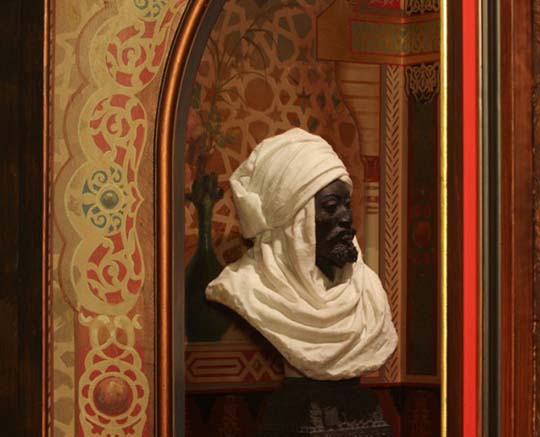

The wall labels make the point that this building was not produced from lakes of inexhaustible wealth. Whilst not done ‘on the cheap’ by any means, financial economies are very evident. Modern building materials such as metal columns have been used, then painted to create the (fleeting) illusion of stone. A trip to Granada inspired Merton and Annie to shoehorn in an utterly random section of Islamic style decoration on one of the upper landings – the ‘Moorish Alcove’. They didn’t have the necessary tiling, so they just had it painted on. It’s pure kitsch fakery, but hard not to love.

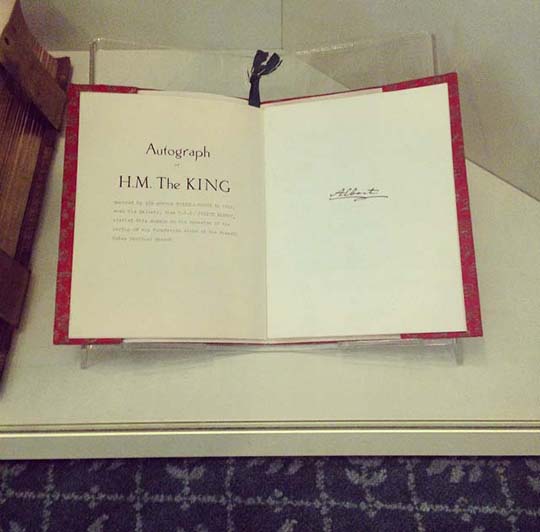

If this house is the portrait of a man, what can we say about Sir Merton? On the face of it, he was an utter conformist. He collected no avant-garde paintings, and admired the popular artists of his day. As a collector it seems he had little intellectual rigour or long term vision, and a magpie’s eye for kitsch. He bought a few good paintings, more by luck than judgement. He was a social climber. Prized among his artefacts are a calligraphic family tree vaingloriously linking him to Alfred the Great, and an enshrined autograph of the King.

Yet there’s more. Underneath it all is a streak of eclectic English eccentricity, which prevents this collection from ever being dull. It’s the image of a man at play, seeking immortality through objects – not just enjoying them for their own sake, but reveling in the wet dream of posterity’s (imagined) handclaps. He didn’t quite leave the world the amazing gallery he was so clearly aiming for. But it’s still rather wonderful.