In 1994, aged seventeen, I went for tea with Gilbert and George.

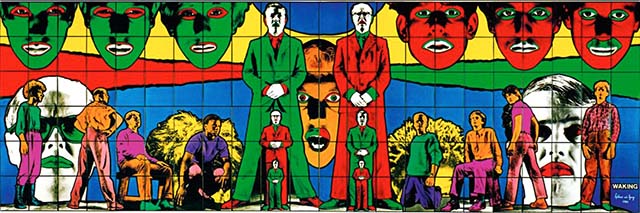

I’d first encountered their work at the tender age of seven. My family was living just outside Dublin and, during a day trip into town, they decided to pay a fleeting visit to a free modern art expo they’d heard about, called ‘Rosc 84’ at the Guinness Hop Store. I was non-plussed and, in some cases, downright terrified by the artists on display. A large Gilbert and George photo piece entitled ‘Waking’ proved an exception though. The grand scale and ultra vibrant colours connected easily with my youthful imagination.

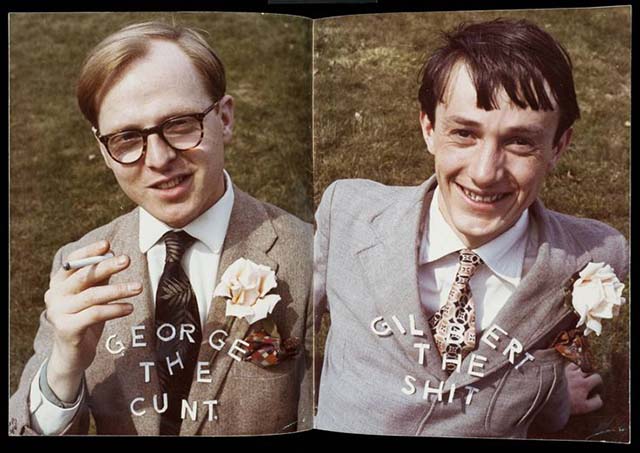

Fast forward a decade, and I found myself remembering my day at Rosc with amazement. I was getting into Conceptual Art, and realised I’d unwittingly had my first taste of a generation of greats that afternoon; Carl Andre, Joseph Beuys, Francesco Clemente, Richard Long… and of course G&G. I excitedly bought Dan Farson’s ‘Gilbert and George in Moscow’ book, and read it with delight. Besides the sheer attention-grabbing vibrancy and scale of their photo pieces, there was a thread of endearing English loopiness that ran through their life and work. They referred to themselves as ‘living sculptures’, and by extension everything they did artistically (even drawings or paintings) was explicitly defined as ‘sculpture’. In their earliest work they pioneered performance art with ‘The Singing Sculpture’. In 1970 they produced a magazine spread featuring themselves wearing silly facial expressions, the slogans ‘Gilbert the Shit’ and ‘George the Cunt’ pinned to their chests. They also went on to experiment with the hilariously self-gratifying category of ‘drinking sculpture’ which consisted of getting pissed on gin and having themselves photographed in various states of inebriation. In short, they were brilliant eccentrics in the very best British tradition.

One day, whilst flicking through a library book on modern art, I noticed a sequence of Gilbert and George ‘postcard sculptures’. Their home address, on London’s Fournier Street, was clearly visible under the heading ‘Art for All’. This slogan intrigued me… if they truly believed art was for everyone did that include me? I now had their address, so I decided to write and say hello.

A week later I received an exuberant note on G&G headed paper from the artists themselves, inviting me round for tea. I called their number to suggest a date and time to visit. The phone rang four times before their answering machine kicked in. George’s clipped public school tones politely invited me to leave a message.

Ten minutes later our phone rang. Mum answered it. “Peter, Gilbert and George are on the phone for you”. Wow. This felt significant and utterly daunting in equal measure. I couldn’t manage much beyond a stuttering monosyllabic conversation – but an arrangement was made for 4pm the following Saturday.

On the big day I took the National Express coach to Victoria, got the tube to Aldgate East and killed a couple of very nervous hours in the Whitechapel Gallery. I trotted down a street of beautiful 18th century townhouses and, physically trembling with trepidation, I finally rang their bell.

Their housekeeper, Stainton Forrest, opened the door and greeted me courteously, albeit with a degree of formal distance. He took my coat and ushered me into the hall. It, like the rest of their house, was immaculately clean, with varnished wooden floors and impeccably tasteful, minimal decor. Stainton invited me to follow him up the stairs to the parlour where, he assured me, Gilbert and George eagerly awaited my presence.

Dressed in exactly the same formal attire I’d always seen them wearing, my two idols stood up in unison to warmly shake my hand and welcome me to their home. They asked me to take a seat, poured me a cup of tea and proffered an array of beautiful cakes on an antique stand.

Gilbert, originally from Italy, still had a strong accent. His manner was more brusque, his questions quick-fire and his wit rather waspish. George, a dyed in the wool upper crust Englishman, spoke more, smiled more, and gave off an altogether more approachable air. He flattered me, praising me for my letter and asking if I was the most intelligent boy in my school. I shrugged and fished around in my bag for the present I’d brought. “I… I made you this” I gulped, handing over a wispy semi-abstract acrylic painting. They gathered round it to sweetly (if a little unconvincingly) heap praise on my brushwork.

“Now anyway”, said George, sitting back down, “what other artists are you interested in?” I paused, in a degree of horror, fearing that this might be a trap. I didn’t want to get it wrong. Perhaps I knew a bit too much about G&G for comfort? I’d read in the Dan Farson book, for example, that anyone who uttered the name of ‘that foreign dago wanker’ (George’s pet name for Picasso) would be physically ejected from the house. Looking back, I can only assume this was a joke, but as a serious teen (and a serious Picasso fan myself) I really didn’t feel I could risk it.

“I just love Francis Bacon!” I said spinelessly, knowing this was a safe bet, as they had been friends.

“Yes, of course… we love Francis too.” We then talked about my career. I explained that I wanted to be an artist, but I also wanted to write.

“You’re unlucky” snapped Gilbert, “You’re good at more than one thing, and that’s a hard burden you know. We were both fortunate. We were crap at everything else we attempted.” The conversation had a surreal air, their utterances a sequence of considered riddles and aphorisms. At times these statements contradicted one other.

“We don’t go to art galleries ourselves” George announced loftily, “When we were students we looked at art, now we work as artists without reference to the work of anyone else.” Fair enough, I nodded.

Later on, however, he described how he’d visited my home town of Bournemouth several times.

“Oh, the gallery there by the sea is a wonderful place! There’s a painting by Frank Brangwyn we love to look at.” He was contradicting himself but I didn’t mind it, then as now – it made them seem a bit more interesting, and gave me the sense that with the second statement George had lifted the mask and offered a slight glimpse behind the (less compelling) official party line.

Conversation paused a moment, and George leapt up with boyish excitement, announcing that he had recently acquired an old leatherbound book that claimed to analyze character types according to their colour preferences. Would I have a try? I was delighted to participate in this fun little diversion. He presented me with a dazzling array of colour swatches, and told to pick one instinctively, without conscious thought. I chose a turquoise shade, and George looked up the corresponding definition.

“Sensitive, and with deep religious feeling” he happily announced. I commented that it seemed to fit me in some ways – my family was religious and my brother was a candidate for the Roman Catholic priesthood. George seemed delighted that his colour test had worked.

The next challenge came from Gilbert.

“Do you know who this is?” he asked sharply, pointing to a framed photo on the mantelpiece. Luckily, I did.

“Yes, it’s the poet David Robilliard.” Robilliard’s name cropped up throughout the literature on G&G – a young gay poet whose work they’d championed until his untimely death from AIDS. Gilbert proceeded, with frequent interjections from George, to tell me about his friend’s work, with obvious passion and sincerity.

“Perhaps”, suggested Gilbert at the end of his mini-eulogy, “you might read us one of his poems?”

“I’d be… er… delighted” I said tentatively. I wasn’t sure what this was going to entail. The prospect of reading aloud in front of my artistic heroes was not an inviting one – I saw only the potential for humiliation, and I wasn’t wrong.

George presented me with a slim hardback volume of poems.

“This one” he said, “read this one”. I looked down and my heart sank.

“P-p-percy Pisshead” I began, feeling utterly humiliated. “Percy Pisshead / Wets the bed / Shits his pants / And craves romance” G&G exchanged glances, and were sniggering before the end of verse one. By the end of the final verse, Gilbert was dabbing little tears of amusement from his eyes. I can’t blame them – my rabbit-in-headlights delivery must have been comedy gold. I only wish I’d been able to appreciate the moment with them.

Hilarity dispensed with, G&G suggested that before I leave they could offer me a tour of their studio. This was more like it. I was very excited to see where the magic took place. They took me round the back of the house into a large room, with adjoining darkrooms.

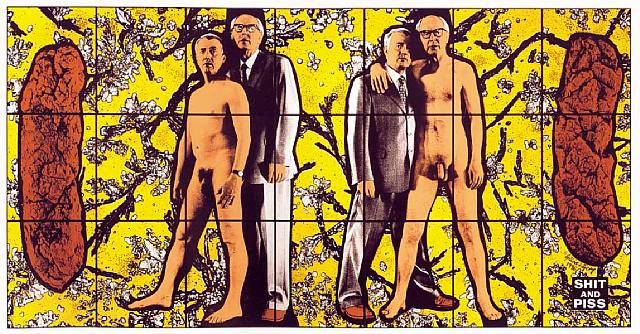

Unsurprisingly given their hard-edged style, the place was not much like a traditional artists studio – it consisted instead of several long tables. They were just beginning work on a new series of images – an embryonic set of photo-pieces that would go on to become ‘The Naked Shit Pictures.’ Little did I know that this would become the most famous sequence in the artists’ career thus far, causing a tabloid sensation and pushing Gilbert and George to a new level of fame. I had the privilege of a first look…

At the time of my visit, these pieces existed as a mass of contact sheets littering one of the studio tables. G&G were in the process of selecting pictures to enlarge, colour up and turn into compositions.

Much as I’d love to say that I was unshockable and super cool (deep down I longed to be), I couldn’t help the fact that I was a rather prudish seventeen year old schoolboy, unaccustomed to appreciating the aesthetic merits of human waste. Unlucky for me then – for the table sagged under the weight of hundreds and hundreds of black and white photographs of shite. I couldn’t believe my tiny eyes.

“Wow”, I stuttered, a tremulous horror evident in my voice.

“The texture is so exciting isn’t it!” exclaimed George with genuine animation, picking up a fisful of contact sheets. “Look at this one… the way it catches the light and glistens… so perfectly formed and beautiful.”

“Mmm…” I didn’t quite know what to say, but I could kind of see what he was talking about. If you managed for a moment to forget what it actually was, you could appreciate it. Yet this was another contradiction, surely, because the eventual photo pieces would positively revel in their… well… shittiness. Overall they seemed determined to shock and confront, not soothe and beguile – and with titles like “Shitty Naked Human World” you could hardly forget what you were seeing. I was definitely getting a sense of mischief from the artists – they’d enjoyed having me read them a naughty poem, and now if I wasn’t much mistaken they seemed to be delighting in showing me their shit and making me blush. My conclusion was that reactions delighted them more than plain aesthetics, despite what George claimed.

We didn’t linger long in the studio, and eventually returned to conclude our chat in the parlour. They gave me a stash of valuable exhibition catalogues as a gift, and promised to stay in touch. George showed me a personal photo archive they kept, documenting every single visitor to Fournier Street. I was honoured to be invited to join those ranks. I posed for a photo between the artists on a small seat. To my eternal regret I never got a copy – but still, just knowing it’s there in their archive is a nice thought.

And that was that. As soon as I got home I excitedly wrote to thank G&G, hoping that this would be the beginning of an ongoing friendship. They never replied, and for a long time after I was rather sad, feeling that they’d perhaps been a bit dishonest with me. A few years ago on the South Bank Show, I heard them explain to Melvyn Bragg that this “one visit and nothing more” was a defined tactic they used with their fans. They explained that so many people wrote to them, they couldn’t possibly befriend everyone – yet nor did they like the idea of ignoring people. In rather a regal manner, their compromise was to grant their fans a one-off audience. These days, enough time has passed for me to be able to confidently say that I’m flattered and delighted they did.