‘a mildewed lump of elephant droppings’ HRH Prince Charles

Everyone had a strong opinion on Portsmouth’s Tricorn shopping centre. In 1967 the Observer architecture critic Ian Nairn raved that it had been “given an architectural orchestration in reinforced concrete that is the equivalent of Berlioz or the 1812 Overture.” The same year it became the first shopping development to win a Civic Trust Architecture award. Yet in surveys of public opinion since the sixties, it was regularly named “the ugliest building in Britain.”

The Tricorn scheme was first hatched in the early sixties. Portsmouth suffered heavily from bombing and, like many other cities, began to make plans to renew and develop its beleaguered centre. In contemporary schemes for New Towns like Stevenage, Cumbernauld, and Basildon, shops, residential and leisure facilities were designed by a single team of architects and built together around a central public space. Portsmouth went for an ambitious new mini-centre along these lines. Architect Owen Luder was commissioned to design one building to meet all of Portsmouth’s needs. It would contain a department store, a supermarket, smaller shops, residential flats, a multi-storey car park, restaurants, bars and the re-housed Commercial Road wholesale market.

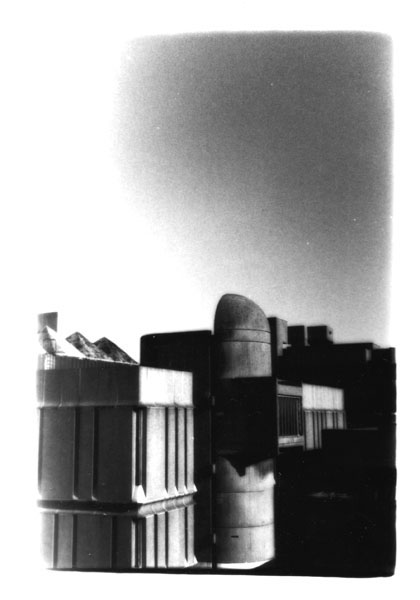

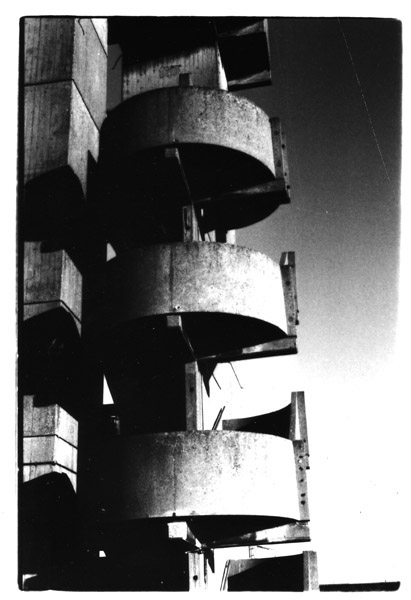

When it opened, though, the new Tricorn centre cut an odd profile across the city. Locals didn’t know what to make of it. No-one could deny it was a dramatic, eye catching structure. Boat-shaped parking decks were stacked against the skyline. Access for cars came via a huge spiral ramp. The entire centre was open to the elements, the walls completely flat and bereft of any applied decoration. The whole piece was executed in concrete, unpainted and unrendered. The walls bore only the slight textures of the wooden shuttering into which the liquid concrete had been poured.

This style, popular with architects in the sixties, was christened “brutalism”, both in recognition of its uncompromising look, and after the French beton brut (unpainted concrete). Le Corbusier had been the first well-known architect to use concrete in this way, on his “Unité d’Habitation” of 1948-54, a huge housing block in Marseilles commissioned on a limited postwar budget. The architect decided that, instead of trying to disguise the harsh economic realities of the period, he would declare them in the structure itself, by refusing to paint, decorate, or smooth out his raw material. This new style of Brutalism enjoyed a brief but all encompassing worldwide postwar vogue, mainly because it was cheap to do. The Tricorn was no exception. It went from a model to a working building in four years and cost only £200,000. The Council needed a quick solution, and they got it very cheap.

According to local newspapers, the official opening of the Tricorn in 1966 was a disaster. The rain bucketed down, gathering in lakes on the uneven surface of the first floor market, while the Lord Mayor made an apologetic speech.

“It looks horrible from the outside” he acknowledged, “but we are not here for things which look pretty, but which work.”

That’s just it, though, the centre didn’t work. By 1969 many shops had still not been let – and the market traders were complaining.

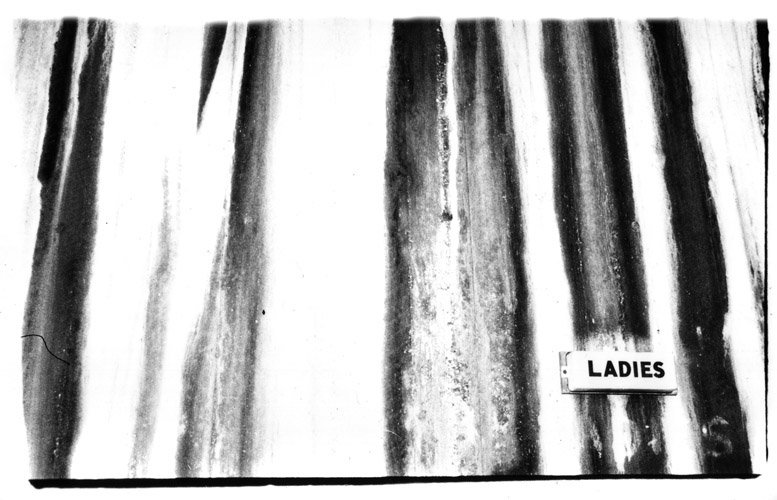

“You can say what you want about Commercial Road,” said Mr Chamberlain, a trader, “but we were happy there”. Grievances about the new site included inadequate drainage, a lack of shelter from the elements, dangerous approach roads and an absence of toilet facilities. The story was just as bad over in the residential blocks. Victor Hogg left the flats in the early seventies.

“It was lovely when we first moved in,” he admitted. “but in less than a year, the walls were black with mould. Come winter everything got damp.”

Portsmouth learnt from its mistakes, and in 1989 unveiled ‘Cascades’, a far slicker, enclosed shopping centre, only a street away from the Tricorn. It cost £100 million, and took the council fifteen years from conception to completion. Heralded as “one of the most complicated planning and development schemes ever undertaken in this country” it won no architectural awards, and no plaudits in the broadsheets. Most importantly, however, it was never voted the ugliest building in Britain.

After Cascades opened, there were a few half-hearted attempts to resurrect the failing Tricorn. In 1993 some of the walls were painted white. Soon after, there was a pathetic attempt to “rebrand” the Tricorn with the Cascades logo. In 1995 however, Rod Vorm, the longest serving trader, admitted defeat and closed his shop. The place was now completely empty, and its fate appeared sealed. A demolition date was set.

Perversely, in a sudden and unexpected twist, some local residents chose this moment to stick up for the centre and demand its preservation. The Portsmouth Society, dedicated to protecting the heritage of the area, applied to English Heritage for a grade II listing, forcing the Council to halt all future plans pending the decision. Portsmouth Society secretary Roger James wrote that the Tricorn was a piece of “sculptural architecture” worthy of preservation.

The Society’s move came at a time when English Heritage was in the throes of a deep re-appraisal of postwar architecture. People began to appreciate the need to protect hitherto maligned structures, lest they lose forever these snapshots of a different era. The early 90s saw Denys Lasdun’s brutalist National Theatre, along with a host of other brutal classics from the Barbican centre to the earliest motorway flyovers, receive a Grade I listing. The Tricorn, however, was not to be so lucky. After some months of deliberation, English Heritage decided that the building was “unsuccessful.”

Various demolition schemes came and went in the late 90s, as the structure continued to rot. The dark, narrow, piss-stinking alleyways engendered a hideous sense of foreboding even during daylight hours. Stalactites began to form under the eaves, giving the place a creepy cave-like feeling. Incidences of suicides in the multi-storey car park were so high that The Samaritans affixed placards on the top level. The whole place was altogether a different world from its sister centre Cascades, only a few metres away. Liberal Democrat MP Mike Hancock summed up emotions when he said “it’s as if there’s a curse on the city from the Tricorn”.

With the rise of the internet, support for the preservation of the space grew stronger, but it changed. It no longer spoke of “beauty” or “sculptural architecture” but focussed on the Tricorn as a kind of symbol for anti-consumerism. Two anonymous Portsmouth writers launched an internet defence of the Tricorn, entitled “Our Brutal Friend”. “Essential to our support”, they wrote, “is that the Tricorn refused to exist as a mute space, a facilitator of an anodyne, seamless shopping experience.” They pointed out that Portsmouth Council had thus far only failed to demolish the hated monolith because they couldn’t stump up the cash to replace it. “The buildings continued existence owes more to the demands of ultra-capitalism than it does to its official heritage value”.

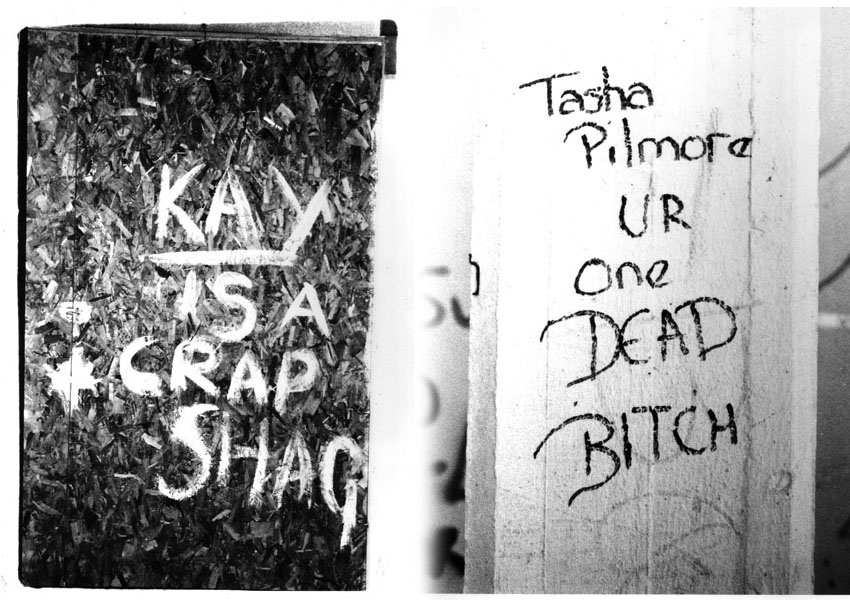

David Ferrone and Martin Fickling, two young film-makers, spent four years documenting the life of the centre. Their film was nominated for an award in Southampton’s Harbour Lights festival. Additionally, the bare walls of the centre offered a vast blank space for graffiti writers in the city. The wall next to the old wholesale market on the first floor became home to a huge multi-coloured mural, sprayed by local people. The spraycan art varied from the funny, scrappy and whimsical to the abstract and beautiful. On the ground floor there grew a separate, bitchy narrative of people and relationships, scrawled in marker pen by bored teenagers.

The story finally reached its conclusion in 2004 when the Tricorn centre was knocked down, despite some last minute fears that the demolition would unleash a horrendous plague of rats and fleas on Portsmouth. Local news played angry scenes of residents arguing with anti-demolition protesters, before applauding and cheering to see the overdue toppling of the “giant pigeon loft” that had blighted their city for nearly forty years.

*

Two months ago the Tricorn’s architect Owen Luder passed away at the age of 93. He outlived most of the buildings he’d designed, and late in life ended up joining the so-called Rubble Club, a slightly tongue-in-cheek support group for bereaved architects whose creations fall victim to the vicissitudes of taste. In the years since I first wrote this article (which sprang originally from a photographic project on my Foundation Course back in 2001), I’ve often wondered if the Tricorn could had survived and found a better future. Brutalism has a huge fan-base these days, with Instagram accounts like @brutal_architecture and @brutgroup attracting thousands of followers, and spinning off into popular coffee table books which celebrate the wild, graphic shapes of this most uncompromising postwar trend. I do think it’s possible the place could have been re-invented.

Yet despite loving the Tricorn myself, and being close to obsessed with it 20 years ago, I remain on the fence about whether it really should have been preserved. It was an extremely strong, eye-catching structure, but unlike many other better known, more Metropolitan examples of Brutalism, I’ve a sneaking suspicion it was just too cheaply made to be saved. Buildings have to work, they’re not there just to look cool on Instagram posts: they have to keep out the rain and be properly accessible. It’s easy for me to sit around rhapsodising about a place like the Tricorn: I didn’t have to live and work there. If Portsmouth council weren’t willing to pour untold millions into repairing its many flaws, I don’t think there was much point keeping it. Having said that – it hasn’t been replaced with anything… 17 years on, the old site is still a thoroughly depressing (and apparently ‘temporary’) ground level car park.

Photos by Peter James Field / Film below by Martin Fickling