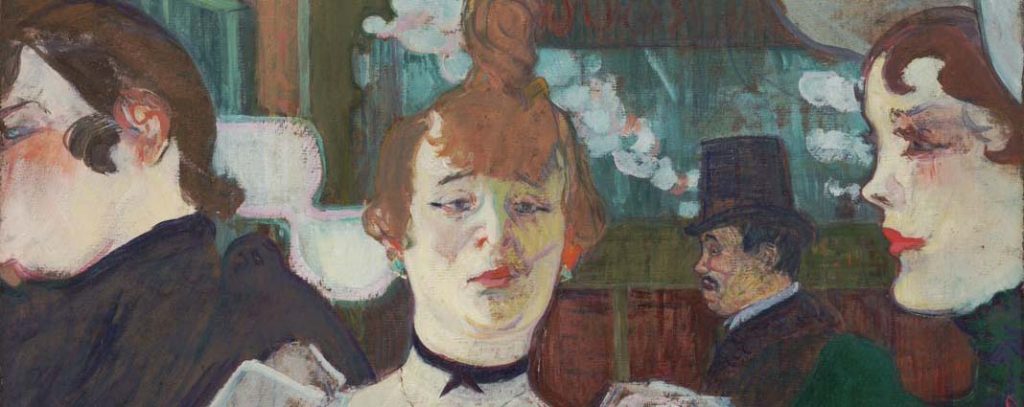

Toulouse Lautrec depicts a haughty woman at the door of the Moulin Rouge, arm in arm with a pair of friends. Her face is not pretty in any classical sense, and her dress is, for the era, very provocative. Her companions are merely framing devices for this snooty character. They are partially cropped out of frame like a photo snapshot. She is the star of this scene. This portrait offers us the earliest glimmer of an as yet undreamt of celebrity culture that was to emerge in the 20th century.

Toulouse-Lautrec was born to an aristocratic family, who gave their name to the French city of Toulouse. He was the heir to a fabulous fortune, the latest in line from a family not without its share of troubles.

Inter-breeding, in this case the marriage of family members to first cousins, is thought to have been the root cause of a series of birth defects which decimated the family by the late 19th century. Toulouse Lautrec himself was a dwarf, and suffered constant pain in his legs. His family expected him to live a life of luxurious leisure and seclusion on the family estate but, fortunately for us, Lautrec wanted more. He spent his confined indoor hours painting, and eventually left for Paris to be an artist, against his fathers wishes. This was no silver spoon situation. When his father learned that he was signing his pictures with the family name, Lautrec was partially disinherited, and his uncle angrily cast his early works on an open bonfire. After a childhood cosseted in material wealth, Lautrec now joined the poverty stricken painters of late 19th century Montmarte.

Lautrec found it difficult to attract a partner. This lead to a fascination with prostitutes, which grew to an obsession (and ended in syphilis). His paintings of prostitutes never seemed idealized or judgemental, though. There is an honesty and tenderness to them. In a great many cases they became his friends.

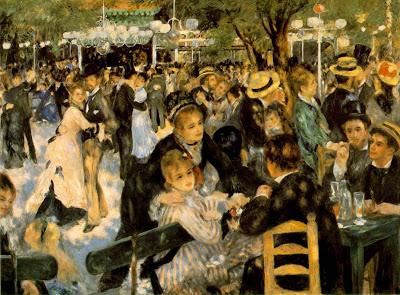

Much of Lautrec’s output documents the vibrant club scene in Paris, delighting openly in the hedonism of it all, whilst never losing the bittersweet edge which suggests he understood its transience, and felt removed from it all somehow. A case in point can be found by comparing Renoir’s fluffy, insipid painting of the Moulin de la Galette dancehall with Lautrec’s later version. It’s hard to believe they are representations of the same club.

Renoir’s picture shimmers with light, the figures all glancing towards the artist in a moment of shared, respectable bonhomie.

Yet in Lautrec’s picture, the figures feel more isolated and the club seems seedier and more claustrophobic. The green glow is slightly sickly and redolent of the dubious pleasures contained in a glass of absinthe – pleasures the artist himself would soon be destroyed by.

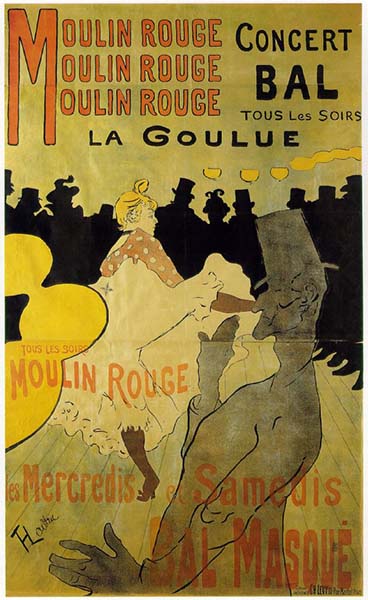

The sitter in our Moulin Rouge portrait is an habitué of seedy Paris night-spots – Louise Weber, known as La Goulue, ‘The Glutton’. We don’t know how she got her nickname. Some believe it was from her buxom figure, while others have cited her greedy propensity to drain the beer glasses of unsuspecting Moulin Rouge punters. Either way, few would disagree that she, like Lautrec, was nursing a growing alcohol addiction.

La Goulue was an early innovator in Parisian dance – a Moulin Rouge regular who popularized a dance that would go on to be known as the can-can. At first she was not even a paid employee of the club. She and her dance partner Valentin le Désossé (Valentine ‘the boneless’ – after his dance style) began as amateurs who quickly gained notoriety. La Goulue had a distinctive look – a contemporary described her as having ‘a vampire’s face, the profile of a bird of prey, a tortured mouth and metallic eyes.’ She quickly became a celebrity in Paris and far beyond, thanks in no small part to Lautrec, who was fascinated by her, and used her distinctive shape in early posters for the Moulin Rouge.

His advertisments for the club are among the first truly memorable mass produced lithographic posters and, in a pre TV and cinema age, brought the club’s stars to a wider audience than any entertainment act had previously known.

The haughty Goulue (despite enjoying her new found success) failed to appreciate the influence Toulouse-Lautrec had wielded over her career – she repeatedly turned down requests to sit from life. The only way the besotted Lautrec could force his muse to pose for an oil painting was to convince the Moulin Rouge staff (who did indeed appreciate his power) to place it in her contract.

Our portrait places the spectator in a kind of fan role, perhaps waiting to catch a glimpse of their idol outside the doors of the club as she strolls in. Not for Lautrec the traditional portrait pose, where the sitter meets us eye to eye in a studio setting. She doesn’t even ‘sit’, she is captured, paparazzi style, as she glides past. The picture shows a fascinating character whose face simultaneously displays arrogance and vulnerable sadness. Apparently she hated it, and it’s easy to see why. She’s not idealized or beautified. And isn’t that a double chin?

Some critics have suggested that the picture was a kind of premonition of the future – showing her not as she looked in 1892 but as she would come to look a decade or two later.

Her story has a sad ending – she self-funded a vainglorious attempt to break free from the Moulin Rouge and set up a travelling dance show, which flopped to leave her an alcoholic destitute. Lautrec’s alcoholism killed him in 1901 but La Goulue lived on until 1928 as an anonymous Parisian street dweller, selling matches outside the club where she once danced.